By Nchongayi Christantus Begealawuh

National dialogues have recently gained traction as vital instruments for peace transformations in Africa. National dialogues are usually initiated to deal with a wide range of issues, including political reforms, constitution making and peacebuilding. They can also be seen as political processes aiming to reach a new social contract between interest groups and community in a country. According to the Berghof Foundation’s national dialogue handbook, there has been a certain level of success in the implementation of national dialogues in African countries such as Morocco, Libya, Tunisia and Egypt. However, this is not to say that national dialogues have been very successful for political reforms and peacebuilding in African as the continent has also witness disappointing results in Kenya, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In any of these cases, the civil society has been very influential. In Tunisia, for example, the national dialogue “quartet” a coalition of civil society groups came together in the summer of 2013 at the time when Tunisia, the birth place of the Arab spring was at the crossroads between democracy and violence. This group successfully drew up a plan of action, that would steer Tunisia away from the path of conflict and move the country towards political compromise. This exemplifies the numerous inherent advantages of national dialogues.

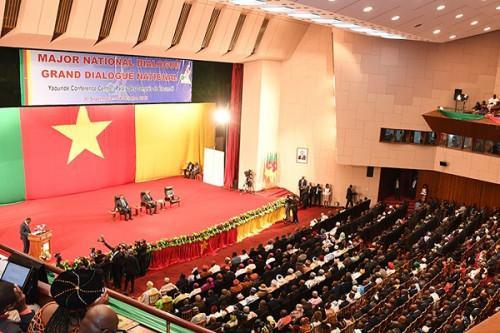

National dialogues can also be used to effectively respond to local actor’s demand for national ownership, inclusion and wider participation. In regions (such as the Horn of Africa region) national dialogues are failing largely because citizens, opposition parties, and the civil society have wanted them but governments haven’t recognized their importance. For example, before the political upheavals that led to the current transition in Ethiopia, several calls for national dialogue by the civil society were ignored. This downplayed the need for reconciliation and national unity. On the other hand, national dialogues initiated by governments with a little push from the civil society has also failed. In South Sudan, the government initiated a national dialogue process in 2017 in the absence of a viable peace agreement on the civil war. The process was largely contested because of its myriad challenges, such as the exclusion of key stakeholders of the conflict and the lack of a conducive environment for “dialogue.” Cameroon’s “Major National Dialogue” announced in 2019 has embedded elements of these two scenarios.

What Makes or Breaks Cameroon’s Major National Dialogue

There are no templates to guide national dialogue processes in general. However, most successful national dialogues have clear structures and well-defined rules and procedures determined by stakeholders or conflicting parties. In any case, most national dialogues (including Cameroon’s Major National Dialogue) go through three stages; preparation, process and implementation.

As far as preparation is concern, successful national dialogues are carefully designed by national stakeholders. In most cases, the intent is to develop a mechanism that will strengthen the society from within. In the case of Cameroon, the National dialogue was entrusted in the hands of Prime Minister Joseph Dion Ngute. The PM led a series of consultations; involving a huge array of national voices, including political skeptics. The preparatory phase also involved influential Catholic leaders such as the late Cardinal Christian Tumi, head of the Anglophone General Conference (AGC)created in 2018. The late Cardinal, who chaired the commission on the assistance of returning refugees and displaced persons during the dialogue and was later designated to lead the peace caravan to the North West region to explain its recommendation, took this as an important opportunity for peacebuilding. However, what breaks the process is the fact that these consultations and preparatory work did not give participating stakeholders enough time to prepare for the major dialogue and the actual process. In addition, many actors consulted had little connection to the main issue, the Anglophone crisis. The Cameroon Major National Dialogue was held three weeks after its announcement, leaving stakeholders consulted with limited time to prepare. This disempowered many participants and weakens the implementation of its outcomes.

Furthermore, as seen in other contexts, the absence of major opposition groups usually casts doubt on the legitimacy and inclusivity in the actual process. When South Sudan’s Salva Kirr launched a national dialogue in May 2017 by a presidential decree, the preparation phase was similarly marked by the absence of major political parties and armed groups, notably the South Sudan People’s Liberation Movement -In-Opposition (SPLM-IO) and former detainees. This process failed because of the exclusion of opposition parties and armed groups. The idea of inclusivity has become a defining factor for national dialogues. As highlighted by Cameroonian journalist Moki Edwin Kindzeka in his write-up with VOA, separatist fighters who were largely absent from the dialogue contend that the dialogue failed woefully, and for peace to return to the English-speaking regions, the government must initiate a “true dialogue.” Thus “inclusivity” affected the Cameroon major national dialogue in many ways and explains why it was a “huge success” for the government and a “complete failure” for separatists and opposition.

Lastly, effective implementation of national dialogue decisions often rests on trust between government, participating stakeholders and civil society. As was the case in South Sudan, the appointment of the national dialogue leadership by the president triggered questions about the independence and neutrality of the process. The opposition and armed groups rejected this appointment and considered it as a deviation from international best practice. This makes implementation difficult. More so, the leadership of the dialogue appointed by the president in the case of South Sudan did not gain popular trust and legitimacy. This contributed to slowing down the implementation of the dialogue’s outcome. What breaks the Cameroon national dialogue is the fact that there was a certain level of mistrust between the civil society and leadership of different commissions created during the actual dialogue. Thus, effective implementation of its recommendation will depend on the level of transparency and public engagement given the trust deficit in the leadership of the process.

467 comments

okmark your blog and check again here frequently. I am quite certain I?ll learn many new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

Hey There. I discovered your blog using msn. This is a really well written article. I?ll make sure to bookmark it and return to learn extra of your helpful info. Thanks for the post. I?ll certainly comeback.

I discovered your weblog web site on google and examine a few of your early posts. Continue to keep up the very good operate. I just additional up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. In search of forward to reading more from you afterward!?

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing this write-up and the rest of the site is also very good.

Nice i really enjoyed reading your blogs. Keep on posting. Thanks

Interesting blog post. The things i would like to bring about is that laptop memory should be purchased in case your computer can’t cope with that which you do by using it. One can put in two random access memory boards of 1GB each, by way of example, but not certainly one of 1GB and one with 2GB. One should check the maker’s documentation for one’s PC to make sure what type of ram is required.

I don?t even know the way I stopped up here, however I assumed this publish was good. I don’t recognize who you are but definitely you’re going to a famous blogger should you aren’t already 😉 Cheers!

After study a few of the weblog posts on your website now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site listing and might be checking back soon. Pls take a look at my web site as properly and let me know what you think.

This design is wicked! You obviously know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Great job. I really loved what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

The information shared is of top quality which has to get appreciated at all levels. Well done…

Audio began playing anytime I opened up this web-site, so irritating!

Many thanks to you for sharing these kind of wonderful content. In addition, the perfect travel plus medical insurance program can often relieve those worries that come with vacationing abroad. A medical crisis can in the near future become costly and that’s certain to quickly set a financial burden on the family finances. Having in place the suitable travel insurance package prior to setting off is well worth the time and effort. Thanks a lot

I will immediately grab your rss as I can not find your e-mail subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Kindly let me know so that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Hiya, I’m really glad I have found this info. Nowadays bloggers publish just about gossips and internet and this is actually annoying. A good website with exciting content, that’s what I need. Thanks for keeping this web site, I will be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can’t find it.

Thank you so much for sharing this wonderful post with us.

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know a lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you could do with a few pics to drive the message home a bit, but other than that, this is magnificent blog. A fantastic read. I’ll certainly be back.

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve visited your blog before but after looking at some of the posts I realized it’s new to me. Regardless, I’m certainly pleased I stumbled upon it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back regularly!

Thanks for your posting on this web site. From my experience, there are times when softening upwards a photograph may provide the photography with a little bit of an artistic flare. Often times however, the soft blur isn’t just what you had at heart and can sometimes spoil an otherwise good photograph, especially if you consider enlarging them.

I have learned some new items from your site about desktops. Another thing I have always assumed is that computer systems have become a product that each home must have for most reasons. They offer convenient ways in which to organize households, pay bills, search for information, study, listen to music as well as watch shows. An innovative technique to complete every one of these tasks is by using a laptop. These desktops are mobile, small, highly effective and mobile.

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after checking through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely delighted I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

Fantastic post however I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Appreciate it!

I’ve really noticed that credit improvement activity has to be conducted with tactics. If not, it’s possible you’ll find yourself destroying your standing. In order to reach your goals in fixing your credit score you have to take care that from this moment you pay all your monthly expenses promptly before their timetabled date. Really it is significant because by not necessarily accomplishing that, all other activities that you will decide to try to improve your credit rating will not be efficient. Thanks for giving your tips.

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyway, just wanted to say fantastic blog!

Good day! Would you mind if I share your blog with my twitter group? There’s a lot of folks that I think would really appreciate your content. Please let me know. Many thanks

It is really a nice and useful piece of info. I am glad that you shared this useful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

I want to to thank you for this excellent read!! I certainly loved every bit of it. I have got you book marked to look at new things you post…

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you penning this post and the rest of the site is extremely good.

A great post without any doubt.

Interesting blog post. What I would like to add is that personal computer memory ought to be purchased if the computer cannot cope with that which you do with it. One can set up two RAM boards with 1GB each, in particular, but not one of 1GB and one having 2GB. One should make sure the maker’s documentation for the PC to be certain what type of ram it can take.

Good post. I learn something totally new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon every day. It will always be exciting to read articles from other writers and use something from other sites.

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you penning this post and the rest of the site is also really good.

There are definitely lots of details like that to take into consideration. That may be a great level to convey up. I offer the ideas above as basic inspiration however clearly there are questions just like the one you deliver up the place crucial thing shall be working in sincere good faith. I don?t know if greatest practices have emerged around issues like that, however I’m sure that your job is clearly identified as a fair game. Both boys and girls really feel the affect of only a second?s pleasure, for the remainder of their lives.

Can I simply say what a reduction to find somebody who actually is aware of what theyre speaking about on the internet. You positively know the way to carry a difficulty to mild and make it important. More individuals need to learn this and perceive this side of the story. I cant believe youre not more widespread since you undoubtedly have the gift.

Excellent goods from you, man. I’ve take into account your stuff previous to and you are just too magnificent. I really like what you have received here, really like what you are stating and the best way wherein you assert it. You make it entertaining and you still care for to keep it smart. I can not wait to read much more from you. That is actually a terrific website.

Excellent post. I will be going through a few of these issues as well..

An additional issue is that video games are generally serious in nature with the major focus on studying rather than enjoyment. Although, it comes with an entertainment feature to keep your young ones engaged, every single game is usually designed to improve a specific set of skills or course, such as numbers or technology. Thanks for your publication.

I am curious to find out what blog platform you happen to be using? I’m experiencing some small security issues with my latest website and I’d like to find something more safe. Do you have any solutions?

magnificent post, very informative. I wonder why the other experts of this sector do not notice this. You must continue your writing. I am confident, you have a huge readers’ base already!

Your style is so unique compared to other folks I’ve read stuff from. Many thanks for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I’ll just book mark this blog.

Great article! We are linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the good writing.

Thanks for the good writeup. It if truth be told was a leisure account it. Look complex to far added agreeable from you! However, how can we keep in touch?

Saved as a favorite, I really like your site.

Hi, i read your blog occasionally and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam remarks? If so how do you reduce it, any plugin or anything you can advise? I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any support is very much appreciated.

I simply couldn’t go away your web site before suggesting that I actually enjoyed the standard info a person supply on your guests? Is gonna be back steadily to investigate cross-check new posts

This site was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something that helped me. Thank you!

I?ll immediately grab your rss feed as I can not find your e-mail subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly let me know in order that I could subscribe. Thanks.

Thanks for your posting. One other thing is that if you are selling your property alone, one of the difficulties you need to be aware of upfront is when to deal with home inspection reports. As a FSBO supplier, the key about successfully moving your property in addition to saving money upon real estate agent revenue is know-how. The more you already know, the smoother your sales effort will likely be. One area where by this is particularly crucial is information about home inspections.

It is appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I have read this post and if I could I want to suggest you some interesting things or tips. Perhaps you can write next articles referring to this article. I wish to read even more things about it!

This is a topic that is near to my heart… Take care! Exactly where are your contact details though?

Thanks for your information on this blog. Just one thing I would want to say is that often purchasing consumer electronics items over the Internet is not new. In truth, in the past decade alone, the market for online electronic products has grown significantly. Today, you’ll find practically any kind of electronic gizmo and gizmo on the Internet, ranging from cameras as well as camcorders to computer spare parts and video gaming consoles.

I would like to thank you for the efforts you have put in penning this site. I’m hoping to view the same high-grade blog posts from you in the future as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own site now 😉

Thanks for the diverse tips discussed on this weblog. I have observed that many insurance companies offer customers generous discounts if they prefer to insure a few cars together. A significant quantity of households have got several cars these days, specifically those with more mature teenage youngsters still living at home, and also the savings with policies can certainly soon mount up. So it will pay to look for a great deal.

I have observed that car insurance organizations know the automobiles which are liable to accidents along with risks. Additionally they know what style of cars are given to higher risk as well as higher risk they have the higher the actual premium fee. Understanding the straightforward basics associated with car insurance can help you choose the right types of insurance policy that will take care of your needs in case you become involved in any accident. Thank you for sharing a ideas on your blog.

I have realized that of all varieties of insurance, health insurance coverage is the most questionable because of the clash between the insurance coverage company’s need to remain adrift and the buyer’s need to have insurance. Insurance companies’ profits on well being plans are very low, consequently some organizations struggle to earn profits. Thanks for the strategies you reveal through this blog.

A fascinating discussion is worth comment. I believe that you ought to publish more about this topic, it may not be a taboo matter but generally folks don’t speak about such subjects. To the next! Many thanks!

I just added this weblog to my rss reader, excellent stuff. Can not get enough!

Excellent write-up. I absolutely appreciate this site. Keep it up!

I really like reading an article that can make people think. Also, many thanks for allowing me to comment.

Would you be all for exchanging links?

I really like your wp design, wherever would you get a hold of it through?

The information shared is of top quality which has to get appreciated at all levels. Well done…

Hello there, I found your site via Google while looking for a related topic, your site came up, it looks good. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

What’s up every one, here every person is sharing these experience, so

it’s pleasant to read this webpage, and I used to pay a visit this

web site everyday.

I’m impressed, I have to admit. Seldom do I encounter a blog that’s equally educative and engaging, and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is something too few people are speaking intelligently about. Now i’m very happy I came across this in my hunt for something relating to this.

Heya i am for the first time here. I found this board and I find It really helpful & it helped me out much. I hope to provide one thing again and help others like you aided me.

Just want to say your article is as surprising.

The clarity in your post is just great and i could assume you’re an expert on this subject.

Fine with your permission let me to grab your RSS feed to keep up

to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please continue the gratifying work.

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog.

En iyi medyum olarak bir danışman için medyum haluk hocayı seçin en iyi medyum hocalardan bir tanesidir.

That is a good tip particularly to those fresh to the blogosphere. Brief but very precise information… Thanks for sharing this one. A must read post.

Heya! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new apple iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the outstanding work!

Thanks for your post on this blog. From my personal experience, often times softening right up a photograph could possibly provide the wedding photographer with an amount of an inventive flare. Many times however, the soft blur isn’t just what exactly you had planned and can frequently spoil an otherwise good photograph, especially if you intend on enlarging them.

After looking into a number of the blog posts on your site, I truly like your technique of writing a blog. I saved it to my bookmark site list and will be checking back soon. Take a look at my website as well and let me know your opinion.

You’re so interesting! I don’t think I’ve truly read through a single thing like that before. So great to discover another person with unique thoughts on this subject. Seriously.. thanks for starting this up. This web site is something that is needed on the web, someone with a little originality.

Excellent post. I am facing many of these issues as well..

It’s hard to find experienced people about this topic, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

It’s best to take part in a contest for top-of-the-line blogs on the web. I will suggest this web site!

Everything is very open with a clear clarification of the challenges. It was really informative. Your site is very helpful. Thanks for sharing.

Hello, I do think your web site could be having internet browser compatibility problems. When I take a look at your web site in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in I.E., it’s got some overlapping issues. I merely wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other than that, great site!

An outstanding share! I have just forwarded this onto a coworker who has been doing a little research on this. And he actually ordered me breakfast due to the fact that I discovered it for him… lol. So allow me to reword this…. Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanx for spending the time to discuss this subject here on your web page.

you’re in reality a just right webmaster. The website loading pace is incredible. It sort of feels that you are doing any unique trick. Also, The contents are masterwork. you have done a wonderful process in this matter!

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve visited this web site before but after looking at many of the articles I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely pleased I found it and I’ll be bookmarking it and checking back often.

Very nice article. I absolutely appreciate this site. Continue the good work!

Excellent web site. A lot of useful info here. I am sending it to a few buddies ans additionally sharing in delicious. And of course, thank you on your sweat!

Your style is very unique compared to other folks I have read stuff from. I appreciate you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I’ll just book mark this page.

I appreciate the research you put into this. It makes your points even more compelling

“Your blog always offers such valuable insights. Keep up the fantastic work!

Thanks for the several tips discussed on this blog. I have observed that many insurance agencies offer buyers generous discounts if they opt to insure more and more cars with them. A significant number of households own several vehicles these days, particularly people with elderly teenage kids still residing at home, plus the savings on policies can soon mount up. So it pays off to look for a good deal.

You should be a part of a contest for one of the greatest sites on the net. I’m going to highly recommend this site!

I’ve shared this with my friends who are interested in [topic]. It sparked a great discussion!

Great site you have got here.. It’s difficult to find quality writing like yours nowadays. I really appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

Howdy! This post could not be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my old room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this write-up to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Many thanks for sharing!

You’re so cool! I don’t suppose I’ve read a single thing like this before. So great to find somebody with some original thoughts on this subject matter. Seriously.. many thanks for starting this up. This website is something that’s needed on the web, someone with a little originality.

Howdy just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your post seem to be running off the screen in Firefox. I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with web browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The design and style look great though! Hope you get the problem solved soon. Cheers

Spot on with this write-up, I absolutely feel this website needs much more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read more, thanks for the information.

Pretty! This has been an incredibly wonderful post. Thanks for supplying this info.

I couldn’t resist commenting. Well written.

I would like to thnkx for the efforts you’ve put in writing this website. I’m hoping the same high-grade web site post from you in the upcoming also. In fact your creative writing skills has inspired me to get my own site now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings fast. Your write up is a good example of it.

Amazing blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A design like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my blog shine. Please let me know where you got your design. Appreciate it

Oh my goodness! Amazing article dude! Thanks, However I am experiencing issues with your RSS. I don’t understand why I am unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone else having identical RSS issues? Anyone that knows the solution will you kindly respond? Thanks!

Thanks for revealing your ideas. I’d also like to state that video games have been actually evolving. Modern technology and revolutions have helped create authentic and enjoyable games. These kinds of entertainment games were not that sensible when the actual concept was first being tried. Just like other designs of know-how, video games also have had to advance through many generations. This itself is testimony for the fast growth and development of video games.

naturally like your website but you have to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very troublesome to tell the truth nevertheless I?ll surely come back again.

Right here is the right blog for everyone who hopes to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost tough to argue with you (not that I actually would want to…HaHa). You certainly put a new spin on a topic which has been discussed for decades. Wonderful stuff, just wonderful.

Good post. I learn something new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon every day. It’s always exciting to read through articles from other authors and use something from other sites.

You need to take part in a contest for one of the most useful websites on the net. I’m going to recommend this site!

Aw, this was an extremely good post. Taking a few minutes and actual effort to generate a really good article… but what can I say… I hesitate a whole lot and don’t manage to get nearly anything done.

Oh my goodness! Incredible article dude! Thank you, However I am encountering difficulties with your RSS. I don’t know why I cannot join it. Is there anyone else getting similar RSS problems? Anybody who knows the solution will you kindly respond? Thanx.

Spot on with this write-up, I seriously feel this website needs a lot more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read through more, thanks for the advice!

This is a great tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere. Short but very accurate info… Appreciate your sharing this one. A must read article.

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I do think that you should write more about this subject, it may not be a taboo subject but usually people do not speak about such issues. To the next! All the best!

Your style is so unique in comparison to other people I have read stuff from. I appreciate you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I’ll just book mark this site.

Fantastic goods from you, man. I’ve keep in mind your stuff prior to and you’re simply too magnificent. I actually like what you’ve obtained right here, certainly like what you are stating and the way in which in which you say it. You are making it enjoyable and you continue to care for to keep it smart. I can not wait to learn far more from you. That is actually a terrific site.

After I originally commented I appear to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now whenever a comment is added I get four emails with the exact same comment. Is there an easy method you are able to remove me from that service? Cheers.

Whats up this is somewhat of off topic but I was wanting to know if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding experience so I wanted to get guidance from someone with experience. Any help would be enormously appreciated!

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this post is awesome, nice written and include approximately all significant infos. I would like to look extra posts like this .

Hello there, I do believe your blog could possibly be having internet browser compatibility problems. Whenever I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine however, if opening in IE, it has some overlapping issues. I merely wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Other than that, wonderful website!

Almanya’nın En iyi medyum olarak bir danışman için medyum haluk hocayı seçin en iyi medyum hocalardan bir tanesidir.

I needed to thank you for this great read!! I absolutely loved every little bit of it. I have you saved as a favorite to look at new stuff you post…

I have realized that car insurance providers know the motors which are liable to accidents along with risks. Additionally they know what type of cars are prone to higher risk and also the higher risk they have the higher your premium price. Understanding the uncomplicated basics connected with car insurance can help you choose the right form of insurance policy that can take care of your preferences in case you happen to be involved in an accident. Many thanks for sharing the particular ideas in your blog.

whoah this weblog is excellent i like studying your posts. Stay up the good work! You know, a lot of people are hunting round for this information, you can aid them greatly.

There is definately a great deal to learn about this subject. I like all the points you’ve made.

I would like to thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this

site. I really hope to check out the same high-grade content

by you later on as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get

my very own site now 😉

ahrareileak, leaked, leakshttps://www.start.gg/user/dc3e79b8

Some tips i have seen in terms of pc memory is the fact that there are features such as SDRAM, DDR etc, that must match the specifications of the mother board. If the personal computer’s motherboard is reasonably current while there are no main system issues, updating the ram literally normally takes under one hour. It’s on the list of easiest laptop or computer upgrade techniques one can envision. Thanks for revealing your ideas.

I couldn’t resist commenting. Perfectly written.

As I site possessor I believe the content matter here is rattling great , appreciate it for your hard work. You should keep it up forever! Good Luck.

With havin so much content do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright violation? My website has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my agreement. Do you know any solutions to help protect against content from being ripped off? I’d genuinely appreciate it.

ahrareileak, leaked, leakshttps://www.start.gg/user/dc3e79b8

I’m impressed, I have to admit. Rarely do I come across a blog that’s both equally educative and engaging, and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head. The problem is something that not enough folks are speaking intelligently about. I’m very happy I found this in my search for something concerning this.

This is hands down one of the best articles I’ve read on this topic! The author’s comprehensive knowledge and enthusiasm for the subject are evident in every paragraph. I’m so thankful for stumbling upon this piece as it has deepened my knowledge and ignited my curiosity even further. Thank you, author, for investing the time to produce such a outstanding article!

Next time I read a blog, I hope that it does not disappoint me as much as this particular one. I mean, Yes, it was my choice to read through, but I actually thought you would have something useful to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could fix if you weren’t too busy looking for attention.

I’m pretty pleased to discover this great site. I want to to thank you for your time due to this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoyed every part of it and I have you book marked to see new stuff on your web site.

I truly love your website.. Excellent colors & theme. Did you make this amazing site yourself? Please reply back as I’m wanting to create my very own blog and would like to find out where you got this from or just what the theme is named. Cheers!

Thanks for your publication on this site. From my own personal experience, many times softening upward a photograph may well provide the wedding photographer with a little bit of an inventive flare. More often than not however, the soft cloud isn’t just what you had in your mind and can often times spoil a normally good photograph, especially if you thinking about enlarging this.

I?ve recently started a website, the info you provide on this site has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

I love it whenever people get together and share thoughts. Great site, keep it up!

It?s actually a nice and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Right here is the perfect website for everyone who wants to find out about this topic. You know so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I personally will need to…HaHa). You certainly put a fresh spin on a topic that has been discussed for many years. Wonderful stuff, just wonderful.

hi!,I like your writing so much! share we keep in touch extra approximately your article on AOL? I require a specialist on this house to unravel my problem. Maybe that’s you! Having a look forward to peer you.

hey there and thank you for your information ? I have definitely picked up anything new from right here. I did alternatively expertise several technical issues the usage of this web site, as I skilled to reload the site a lot of instances prior to I may get it to load properly. I have been brooding about in case your web hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but slow loading instances occasions will often have an effect on your placement in google and can injury your quality ranking if ads and ***********|advertising|advertising|advertising and *********** with Adwords. Well I am adding this RSS to my e-mail and can look out for much extra of your respective interesting content. Ensure that you update this again very soon..

Thanks for the write-up. My spouse and i have always noticed that many people are eager to lose weight as they wish to appear slim and attractive. Nonetheless, they do not usually realize that there are other benefits for losing weight as well. Doctors claim that fat people experience a variety of health conditions that can be perfectely attributed to their excess weight. The good news is that people who sadly are overweight along with suffering from various diseases can help to eliminate the severity of their particular illnesses by means of losing weight. It is possible to see a continuous but noted improvement with health while even a moderate amount of weight loss is reached.

Thanks for your post. Another element is that just being a photographer consists of not only problems in catching award-winning photographs and also hardships in establishing the best dslr camera suited to your needs and most especially issues in maintaining the grade of your camera. It is very correct and clear for those photography lovers that are in capturing this nature’s interesting scenes — the mountains, the actual forests, the actual wild or seas. Visiting these daring places definitely requires a digicam that can surpass the wild’s nasty setting.

A great post without any doubt.

Hi, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot of spam feedback? If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can recommend? I get so much lately it’s driving me mad so any help is very much appreciated.

I would also like to add that if you do not surely have an insurance policy otherwise you do not participate in any group insurance, you could possibly well gain from seeking the aid of a health insurance professional. Self-employed or people with medical conditions usually seek the help of the health insurance brokerage. Thanks for your text.

equipacion tottenham

Spot on with this write-up, I really believe that this amazing site needs a great deal more attention. I’ll probably be returning to see more, thanks for the information!

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it doesn’t disappoint me as much as this particular one. I mean, Yes, it was my choice to read, but I genuinely believed you would probably have something interesting to talk about. All I hear is a bunch of complaining about something you could fix if you were not too busy seeking attention.

Can I just say what a relief to find somebody who genuinely knows what they’re talking about over the internet. You actually realize how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More and more people must check this out and understand this side of your story. I was surprised that you aren’t more popular given that you certainly possess the gift.

Hey! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any tips?

Excellent web site. Plenty of helpful info here. I am sending it to a few friends ans additionally sharing in delicious. And of course, thank you to your effort!

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it does not disappoint me just as much as this particular one. After all, I know it was my choice to read through, however I truly thought you’d have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something that you could possibly fix if you weren’t too busy searching for attention.

I haven?t checked in here for some time as I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are great quality so I guess I will add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

I do agree with all of the ideas you’ve presented for your post. They’re really convincing and will certainly work. Nonetheless, the posts are very quick for beginners. Could you please lengthen them a little from next time? Thank you for the post.

This blog was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something that helped me. Appreciate it.

https://theblockchainland.com/2019/05/24/alibabas-intellectual-property-system-blockchain/

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something like this before. So nice to search out anyone with some authentic thoughts on this subject. realy thank you for starting this up. this web site is one thing that’s wanted on the web, somebody with a little bit originality. helpful job for bringing one thing new to the internet!

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this article is awesome, nice written and include approximately all significant infos. I would like to see more posts like this.

Hey there! Would you mind if I share your blog with my

twitter group? There’s a lot of people that I think would really enjoy your content.

Please let me know. Many thanks

Today, with all the fast chosen lifestyle that everyone leads, credit cards get this amazing demand throughout the market. Persons from every arena are using the credit card and people who aren’t using the credit cards have prepared to apply for one in particular. Thanks for expressing your ideas in credit cards.

In this grand pattern of things you secure an A+ for effort and hard work. Exactly where you actually lost everybody was in the facts. You know, they say, details make or break the argument.. And it couldn’t be much more true at this point. Having said that, allow me say to you just what did deliver the results. The text is definitely highly convincing and that is probably why I am making the effort to opine. I do not make it a regular habit of doing that. 2nd, although I can easily see the leaps in reason you come up with, I am not necessarily certain of just how you appear to connect your details which in turn produce the conclusion. For the moment I shall yield to your point however hope in the near future you actually connect your facts much better.

camiseta de suiza 2022

I have realized that over the course of making a relationship with real estate entrepreneurs, you’ll be able to come to understand that, in every real estate financial transaction, a commission is paid. Ultimately, FSBO sellers will not “save” the payment. Rather, they fight to earn the commission by means of doing an agent’s job. In the process, they shell out their money plus time to conduct, as best they will, the responsibilities of an representative. Those duties include revealing the home through marketing, presenting the home to all buyers, making a sense of buyer emergency in order to trigger an offer, scheduling home inspections, dealing with qualification inspections with the lender, supervising fixes, and aiding the closing of the deal.

jeetwin login

I blog often and I seriously appreciate your information. Your article has truly peaked my interest. I will take a note of your blog and keep checking for new details about once a week. I subscribed to your RSS feed as well.

all the time i used to read smaller posts that also clear

their motive, and that is also happening with this paragraph which I am

reading now.

If some one wants to be updated with most recent technologies

after that he must be pay a visit this website and be up to date everyday.

I figured out more something totally new on this weight loss issue. One issue is a good nutrition is extremely vital while dieting. A big reduction in fast foods, sugary foodstuff, fried foods, sweet foods, pork, and white-colored flour products can be necessary. Possessing wastes bloodsuckers, and toxins may prevent goals for losing fat. While specified drugs for the short term solve the situation, the horrible side effects usually are not worth it, and they never supply more than a momentary solution. It is a known fact that 95 of fad diet plans fail. Thank you for sharing your opinions on this weblog.

I’m very happy to read this. This is the kind of manual that needs to be given and not the random misinformation that is at the other blogs. Appreciate your sharing this best doc.

This is a topic which is close to my heart… Many thanks! Exactly where are your contact details though?

Wow! This could be one particular of the most beneficial blogs We’ve ever arrive across on this subject. Basically Great. I am also a specialist in this topic therefore I can understand your effort.

Wonderful post! We will be linking to this particularly great article on our website. Keep up the good writing.

온라인카지노

great submit, very informative. I wonder why the other experts of this sector do not understand this. You must continue your writing. I am confident, you’ve a huge readers’ base already!

I believe that avoiding packaged foods is a first step to help lose weight. They might taste good, but highly processed foods include very little vitamins and minerals, making you eat more only to have enough energy to get through the day. When you are constantly consuming these foods, changing to grain and other complex carbohydrates will help you have more energy while ingesting less. Good blog post.

The very next time I read a blog, I hope that it won’t fail me just as much as this one. I mean, Yes, it was my choice to read through, nonetheless I genuinely believed you would probably have something helpful to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about something you could possibly fix if you were not too busy seeking attention.

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon every day. It’s always exciting to read content from other authors and practice something from their websites.

I’m impressed, I have to admit. Seldom do I come across a blog that’s both equally educative and engaging, and without a doubt, you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is something that too few people are speaking intelligently about. I am very happy that I stumbled across this in my hunt for something relating to this.

I’m amazed, I must say. Rarely do I come across a blog that’s equally educative and interesting, and without a doubt, you’ve hit the nail on the head. The issue is an issue that not enough people are speaking intelligently about. Now i’m very happy that I stumbled across this in my hunt for something concerning this.

Hello! I just want to give you a huge thumbs up for the great information you have got right here on this post. I am returning to your blog for more soon.

mail me on “ageofz8899@outlook.com”

Wow! This could be one particular of the most helpful blogs We’ve ever arrive across on this subject. Actually Wonderful. I’m also a specialist in this topic so I can understand your hard work.

Thank you for some other excellent article. The place else could anybody get that kind of information in such an ideal method of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I am at the search for such information.

I just could not depart your site before suggesting that I extremely enjoyed the standard information a person provide for your visitors? Is gonna be back often in order to check up on new posts

I’m not sure why but this blog is loading very slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a problem on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Howdy! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone 4! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the superb work!

I love it when people get together and share views. Great website, continue the good work.

That is a good tip especially to those new to the blogosphere. Brief but very accurate info… Appreciate your sharing this one. A must read article.

I really like it when folks come together and share thoughts. Great site, stick with it.

hello there and thank you for your information ? I have definitely picked up something new from right here. I did however expertise some technical issues using this website, since I experienced to reload the site many times previous to I could get it to load properly. I had been wondering if your hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but slow loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google and can damage your quality score if ads and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I am adding this RSS to my e-mail and can look out for a lot more of your respective interesting content. Ensure that you update this again soon..

This is a topic which is close to my heart… Thank you! Where are your contact details though?

Very nice write-up. I absolutely appreciate this website. Keep writing!

Having read this I believed it was extremely enlightening. I appreciate you spending some time and energy to put this article together. I once again find myself spending a significant amount of time both reading and posting comments. But so what, it was still worth it.

Thanks for your helpful article. One other problem is that mesothelioma cancer is generally attributable to the breathing of materials from asbestos fiber, which is a cancer causing material. It’s commonly witnessed among individuals in the construction industry who definitely have long experience of asbestos. It’s also caused by living in asbestos covered buildings for long periods of time, Family genes plays a huge role, and some people are more vulnerable on the risk than others.

I quite like looking through an article that can make people think. Also, thank you for permitting me to comment.

Hey there! I just want to offer you a big thumbs up for your great information you’ve got here on this post. I’ll be returning to your blog for more soon.

Greetings! Very useful advice within this article! It is the little changes that will make the most important changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

Hello there, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. Whenever I look at your blog in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in IE, it has some overlapping issues. I simply wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Aside from that, great site.

I do not even know how I finished up here, however I thought this submit was great. I do not recognise who you’re however definitely you are going to a famous blogger if you happen to are not already 😉 Cheers!

You are so awesome! I do not think I have read through something like that before. So great to discover someone with some unique thoughts on this topic. Seriously.. many thanks for starting this up. This web site is something that is needed on the internet, someone with a bit of originality.

It?s actually a great and helpful piece of info. I?m glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

Very good information. Lucky me I recently found your website by accident (stumbleupon). I’ve bookmarked it for later.

I appreciate, cause I found exactly what I was looking for. You have ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

Oh my goodness! an incredible article dude. Thank you Nevertheless I’m experiencing subject with ur rss . Don?t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting identical rss drawback? Anyone who knows kindly respond. Thnkx

Oh my goodness! Amazing article dude! Thanks, However I am experiencing issues with your RSS. I don’t understand why I can’t subscribe to it. Is there anybody having the same RSS issues? Anybody who knows the solution will you kindly respond? Thanx.

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular article! It’s the little changes that make the most important changes. Many thanks for sharing!

Your style is really unique in comparison to other people I have read stuff from. Thanks for posting when you’ve got the opportunity, Guess I’ll just book mark this blog.

I was just searching for this information for a while. After 6 hours of continuous Googleing, finally I got it in your website. I wonder what is the lack of Google strategy that don’t rank this type of informative websites in top of the list. Normally the top sites are full of garbage.

Your style is really unique compared to other folks I have read stuff from. Many thanks for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just book mark this web site.

Can I just say what a comfort to find somebody who really knows what they are discussing on the net. You certainly understand how to bring a problem to light and make it important. More and more people ought to read this and understand this side of your story. I can’t believe you’re not more popular since you certainly possess the gift.

Everything is very open with a precise explanation of the issues. It was really informative. Your site is extremely helpful. Thanks for sharing.

Very good information. Lucky me I came across your blog by accident (stumbleupon). I have book marked it for later!

I couldn’t refrain from commenting. Exceptionally well written!

Greetings, I believe your blog could possibly be having web browser compatibility issues. When I take a look at your website in Safari, it looks fine however, if opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping issues. I simply wanted to give you a quick heads up! Besides that, excellent website!

After I originally left a comment I seem to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now every time a comment is added I get 4 emails with the same comment. Is there a way you are able to remove me from that service? Cheers.

I was more than happy to find this site. I want to to thank you for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely savored every bit of it and I have you saved to fav to look at new information on your blog.

wonderful put up, very informative. I’m wondering why the other experts of this sector don’t realize this. You must continue your writing. I am confident, you have a huge readers’ base already!

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you penning this write-up plus the rest of the site is very good.

Having read this I believed it was really enlightening. I appreciate you finding the time and energy to put this information together. I once again find myself personally spending way too much time both reading and posting comments. But so what, it was still worth it.

Thanks for giving your ideas. A very important factor is that learners have an alternative between national student loan along with a private student loan where it can be easier to go with student loan debt consolidation loan than over the federal education loan.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve visited this web site before but after looking at many of the articles I realized it’s new to me. Regardless, I’m certainly happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking it and checking back often.

Your style is really unique compared to other folks I have read stuff from. Thank you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just bookmark this web site.

Excellent site you have got here.. It’s difficult to find excellent writing like yours nowadays. I seriously appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

Can I simply say what a relief to find an individual who genuinely knows what they are discussing online. You certainly realize how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More and more people need to look at this and understand this side of the story. I was surprised you’re not more popular since you definitely have the gift.

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it doesn’t fail me just as much as this particular one. After all, I know it was my choice to read, however I actually believed you would probably have something useful to talk about. All I hear is a bunch of crying about something you could fix if you weren’t too busy looking for attention.

F*ckin? amazing things here. I?m very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i’m looking forward to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a mail?

Hi, I do believe this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I am going to return yet again since i have book-marked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide others.

Hello there, just become alert to your weblog through Google, and located that it’s truly informative. I am gonna be careful for brussels. I will be grateful if you continue this in future. Lots of people will likely be benefited out of your writing. Cheers!

Good site you have got here.. It’s hard to find high-quality writing like yours nowadays. I truly appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

I want to to thank you for this fantastic read!! I definitely enjoyed every bit of it. I have got you bookmarked to look at new stuff you post…

I used to be able to find good info from your blog posts.

Oh my goodness! Awesome article dude! Many thanks, However I am having troubles with your RSS. I don’t understand the reason why I can’t subscribe to it. Is there anybody having identical RSS issues? Anyone that knows the solution will you kindly respond? Thanx!!

Hi, I do believe this is a great blog. I stumbledupon it 😉 I may revisit yet again since i have book marked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may you be rich and continue to help other people.

호치민 가라오케

There’s definately a lot to learn about this topic. I really like all the points you have made.

This is a topic which is close to my heart… Thank you! Where can I find the contact details for questions?

I quite like reading through an article that will make men and women think. Also, thank you for allowing me to comment.

What an eye-opening and meticulously-researched article! The author’s thoroughness and ability to present intricate ideas in a understandable manner is truly praiseworthy. I’m extremely impressed by the depth of knowledge showcased in this piece. Thank you, author, for providing your wisdom with us. This article has been a true revelation!

I just added this web site to my feed reader, excellent stuff. Can’t get enough!

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do some research about this. We got a grab a book from our area library but I think I learned more from this post. I’m very glad to see such wonderful info being shared freely out there.

You should be a part of a contest for one of the finest sites on the net. I most certainly will recommend this web site!

Having read this I thought it was really informative. I appreciate you finding the time and energy to put this information together. I once again find myself personally spending a lot of time both reading and commenting. But so what, it was still worthwhile.

This website was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something which helped me. Cheers.

It’s hard to find educated people on this subject, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

https://xn--lg3bul62mlrndkfq2f.com/ed98b8ecb998ebafbc-ec9785ecb2b4/ed98b8ecb998ebafbc-ebb688eab1b4eba788/

This is really interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your magnificent post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social networks!

I have discovered some new issues from your internet site about personal computers. Another thing I have always believed is that computers have become a specific thing that each home must have for several reasons. They supply you with convenient ways in which to organize the home, pay bills, go shopping, study, hear music and also watch shows. An innovative approach to complete many of these tasks has been a mobile computer. These computers are mobile, small, strong and easily transportable.

After exploring a few of the articles on your web site, I seriously appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back soon. Take a look at my web site as well and tell me how you feel.

Spot on with this write-up, I absolutely believe this website needs a great deal more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read through more, thanks for the advice!

Very good information. Lucky me I found your site by accident (stumbleupon). I have book marked it for later!

That is a great tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere. Simple but very accurate info… Thanks for sharing this one. A must read article.

I have seen that fees for internet degree pros tend to be a terrific value. For example a full 4-year college Degree in Communication with the University of Phoenix Online consists of Sixty credits at $515/credit or $30,900. Also American Intercontinental University Online makes available Bachelors of Business Administration with a whole study course feature of 180 units and a worth of $30,560. Online studying has made obtaining your education been so detailed more than before because you may earn your degree through the comfort of your home and when you finish from work. Thanks for all your other tips I have certainly learned through the site.

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this post is amazing, nice written and include almost all significant infos. I?d like to see more posts like this.

One thing I’ve noticed is the fact there are plenty of fallacies regarding the financial institutions intentions whenever talking about foreclosed. One fantasy in particular is the fact that the bank needs to have your house. The bank wants your hard earned money, not the house. They want the amount of money they lent you along with interest. Preventing the bank will only draw a foreclosed conclusion. Thanks for your article.

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your site and in accession capital to assert that I acquire actually enjoyed account your blog posts. Anyway I will be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently rapidly.

Heya i am for the first time here. I found this board and I find It truly useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and aid others like you helped me.

You could certainly see your skills in the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe. Always go after your heart.

I’m not sure why but this blog is loading incredibly slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later and see if the problem still exists.

I do agree with all the ideas you have presented in your post. They are very convincing and can certainly work. Nonetheless, the posts are very short for starters. May just you please extend them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.

Oh my goodness! Incredible article dude! Thank you, However I am having difficulties with your RSS. I don’t understand the reason why I am unable to join it. Is there anyone else having similar RSS issues? Anyone who knows the answer can you kindly respond? Thanx.

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz respond as I’m looking to create my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. thanks

I seriously love your blog.. Pleasant colors & theme. Did you develop this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m planning to create my own site and would love to learn where you got this from or exactly what the theme is named. Kudos!

Would you be considering exchanging links?

This is a topic that’s near to my heart… Take care! Exactly where are your contact details though?

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you writing this write-up and the rest of the website is also really good.

I was more than happy to uncover this page. I wanted to thank you for your time due to this fantastic read!! I definitely appreciated every part of it and i also have you saved as a favorite to look at new stuff on your web site.

I’m amazed by the quality of this content! The author has clearly put a tremendous amount of effort into investigating and organizing the information. It’s exciting to come across an article that not only offers helpful information but also keeps the readers hooked from start to finish. Great job to him for making such a masterpiece!

Top Stage Hypnotist for hire Kristian von Sponneck performs private stage hypnosis shows anywhere in the UK, Europe or worldwide. Hire hime for your next event!

One thing I want to say is the fact before purchasing more laptop or computer memory, consider the machine into which it would be installed. When the machine is definitely running Windows XP, for instance, a memory ceiling is 3.25GB. Applying greater than this would basically constitute just a waste. Make sure that one’s motherboard can handle an upgrade amount, as well. Thanks for your blog post.

Top Stage Hypnotist for hire Kristian von Sponneck performs private stage hypnosis shows anywhere in the UK, Europe or worldwide. Hire hime for your next event!

Pretty! This was an extremely wonderful post. Thanks for supplying this information.

Hey! Someone in my Facebook group shared this website with us so I came to check it out. I’m definitely enjoying the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Wonderful blog and excellent style and design.

There is definately a lot to learn about this topic. I like all of the points you’ve made.

Everything is very open with a really clear description of the issues. It was definitely informative. Your site is extremely helpful. Thank you for sharing!

Spot on with this write-up, I truly believe this amazing site needs a great deal more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read more, thanks for the advice!

Great site you have here.. It’s hard to find high quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

I blog frequently and I truly thank you for your information. This great article has truly peaked my interest. I will take a note of your website and keep checking for new details about once per week. I subscribed to your Feed too.

Howdy! This blog post couldn’t be written any better! Going through this post reminds me of my previous roommate! He continually kept preaching about this. I’ll send this information to him. Fairly certain he’s going to have a very good read. Thanks for sharing!

The next time I read a blog, I hope that it does not disappoint me as much as this particular one. After all, I know it was my choice to read through, but I really thought you’d have something helpful to say. All I hear is a bunch of crying about something you can fix if you weren’t too busy looking for attention.

Very good article. I will be dealing with many of these issues as well..

You are so cool! I don’t think I’ve truly read through anything like that before. So great to find another person with some unique thoughts on this topic. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This website is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with some originality.

After exploring a handful of the blog articles on your web page, I really like your technique of blogging. I book-marked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back in the near future. Take a look at my web site too and tell me how you feel.

I need to to thank you for this very good read!! I absolutely enjoyed every bit of it. I’ve got you saved as a favorite to check out new things you post…

hello there and thank you for your information ? I?ve certainly picked up anything new from right here. I did however expertise a few technical issues using this site, as I experienced to reload the web site lots of times previous to I could get it to load correctly. I had been wondering if your hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will often affect your placement in google and could damage your quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I?m adding this RSS to my email and can look out for much more of your respective intriguing content. Make sure you update this again very soon..

One thing is that while you are searching for a student loan you may find that you’ll want a co-signer. There are many scenarios where this is correct because you could find that you do not have a past credit score so the loan company will require you have someone cosign the financial loan for you. Good post.

F*ckin? tremendous things here. I?m very happy to peer your post. Thanks so much and i’m having a look ahead to contact you. Will you please drop me a mail?

I feel that is among the so much vital info for me. And i’m happy studying your article. But want to remark on some normal issues, The site style is great, the articles is in point of fact nice : D. Good activity, cheers

After going over a handful of the blog posts on your website, I seriously appreciate your technique of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark webpage list and will be checking back soon. Take a look at my website too and let me know how you feel.

I have seen that costs for on-line degree gurus tend to be an incredible value. For example a full Bachelors Degree in Communication with the University of Phoenix Online consists of 60 credits with $515/credit or $30,900. Also American Intercontinental University Online offers a Bachelors of Business Administration with a complete program element of 180 units and a price of $30,560. Online degree learning has made getting your degree been so detailed more than before because you can earn the degree from the comfort of your dwelling place and when you finish working. Thanks for all other tips I’ve learned from your blog.

A person essentially help to make seriously posts I would state. This is the very first time I frequented your web page and thus far? I surprised with the research you made to create this particular publish incredible. Magnificent job!

I was very happy to uncover this great site. I want to to thank you for your time just for this wonderful read!! I definitely appreciated every part of it and i also have you saved as a favorite to check out new things on your blog.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this web site before but after going through many of the articles I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely delighted I discovered it and I’ll be bookmarking it and checking back often.

Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular article! It’s the little changes that make the most significant changes. Thanks for sharing!

Aw, this was a really nice post. Spending some time and actual effort to make a superb article… but what can I say… I procrastinate a lot and don’t seem to get nearly anything done.

Great site you’ve got here.. It’s hard to find good quality writing like yours nowadays. I honestly appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

Good site you have here.. It’s difficult to find excellent writing like yours these days. I honestly appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

An impressive share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a colleague who has been conducting a little homework on this. And he actually bought me lunch simply because I discovered it for him… lol. So allow me to reword this…. Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending the time to talk about this subject here on your site.

Simply desire to say your article is as surprising. The clarity for your publish is simply great and i can assume you’re an expert on this subject. Fine along with your permission let me to grasp your RSS feed to keep up to date with imminent post. Thanks a million and please continue the enjoyable work.

Hi, I do believe this is a great site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I’m going to return once again since i have bookmarked it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide others.

Good post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon on a daily basis. It will always be helpful to read through content from other writers and use something from other web sites.

Spot on with this write-up, I absolutely feel this site needs much more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read more, thanks for the information!

I know of the fact that nowadays, more and more people are being attracted to camcorders and the area of pictures. However, as a photographer, you will need to first expend so much of your time deciding the exact model of photographic camera to buy as well as moving store to store just so you can buy the least expensive camera of the brand you have decided to choose. But it won’t end right now there. You also have take into consideration whether you can purchase a digital digital camera extended warranty. Thx for the good ideas I gained from your weblog.

https://standupforsouthport.com/?subject=Southport FC thrashed 5-0 by Chester City as Sandgrounders aim to bounce back on Tuesday&body=https://standupforsouthport.com/southport-fc-thrashed-5-0-by-chester-city-as-sandgrounders-aim-to-bounce-back-on-tuesday

https://peachtree-online.com/2010/02/where-do-your-manuscripts-go-and-other-fun-facts-2/?replytocom=1269295

Hi there, I found your web site via Google while looking for a related topic, your site came up, it looks great. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

You’re so interesting! I do not suppose I’ve read through something like that before. So good to discover somebody with a few unique thoughts on this subject matter. Really.. many thanks for starting this up. This website is something that is needed on the web, someone with a little originality.

That is the best blog for anybody who wants to seek out out about this topic. You notice a lot its nearly laborious to argue with you (not that I truly would want?HaHa). You undoubtedly put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, just great!

My brother recommended I might like this blog. He was entirely right. This post actually made my day. You can not imagine simply how much time I had spent for this info! Thanks!

Excellent article! We will be linking to this great article on our website. Keep up the great writing.

Good article. It’s very unfortunate that over the last one decade, the travel industry has already been able to to take on terrorism, SARS, tsunamis, influenza, swine flu, and also the first ever entire global economic downturn. Through all of it the industry has proven to be solid, resilient along with dynamic, getting new solutions to deal with difficulty. There are constantly fresh challenges and chance to which the marketplace must once again adapt and answer.

Thanks for enabling me to get new thoughts about pc’s. I also contain the belief that certain of the best ways to maintain your laptop in excellent condition has been a hard plastic-type material case, or perhaps shell, that fits over the top of one’s computer. A lot of these protective gear are generally model unique since they are manufactured to fit perfectly on the natural housing. You can buy them directly from the vendor, or via third party places if they are intended for your notebook computer, however not all laptop could have a cover on the market. Once again, thanks for your recommendations.

Hi, There’s no doubt that your website could be having browser compatibility problems. Whenever I take a look at your blog in Safari, it looks fine however, if opening in IE, it’s got some overlapping issues. I merely wanted to give you a quick heads up! Apart from that, wonderful site.

Wow, incredible blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your site is fantastic, as well as the content!

Thanks , I’ve just been looking for information about this topic for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what about the bottom line? Are you sure about the source?

Hi, I do believe this is an excellent blog. I stumbledupon it 😉 I am going to revisit once again since i have saved as a favorite it. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to guide others.

I cherished as much as you will receive carried out proper here. The cartoon is attractive, your authored subject matter stylish. however, you command get got an impatience over that you wish be handing over the following. sick indisputably come more previously again as exactly the similar nearly a lot regularly within case you shield this hike.

I used to be able to find good info from your blog articles.

I love reading through an article that will make people think. Also, many thanks for allowing me to comment.

An outstanding share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a co-worker who was conducting a little research on this. And he in fact bought me lunch because I found it for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending the time to talk about this topic here on your web site.